The most common disease confused with pulmonary arterial hypertension is diastolic heart failure (also called heart failure with preserved ejection fraction-HeFPEF). In my practice about 70% of patients referred to me for PAH actually have diastolic heart failure.

The most common disease confused with pulmonary arterial hypertension is diastolic heart failure (also called heart failure with preserved ejection fraction-HeFPEF). In my practice about 70% of patients referred to me for PAH actually have diastolic heart failure.

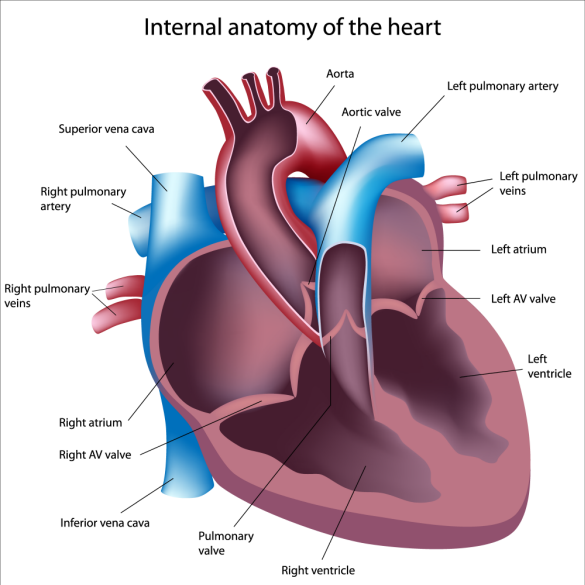

Let’s review basic heart function. The heart has two main actions—squeezing and relaxing. The squeezing phase is called systole and the relaxation phase is referred to as diastole. The squeezing of the heart pumps blood into the aorta (the largest artery in your body). During the relaxation phase blood returns to the heart so that during the next squeeze cycle there is blood to pump. In the past, most patients with heart failure had systolic dysfunction or weakening of the pumping phase. However, as medicines to treat and prevent heart attacks have improved, we are seeing much less systolic dysfunction. In contrast, we are now seeing much more diastolic heart failure.

What are the common risk factors for getting diastolic heart failure?

- Older age

- Being a woman

- Obesity

- Diabetes

- Hypertension

- Coronary artery disease

- Obstructive sleep apnea

- Atrial fibrillation

In my experience the most important modifiable risk factor (attribute that we can change) is obesity. Many of the other risk factors are either caused by or worsened by being overweight. For example, diabetes, sleep apnea and hypertension are all exacerbated or caused by weight gain.

What are the symptoms of diastolic heart failure?

The most important symptom is shortness of breath. Patients also experience fatigue, leg swelling, abdominal swelling. Less common symptoms include chest pain and cough. Patients may become uncomfortable when lying down flat and find that they are propping themselves up on pillows or sleeping in a reclining chair.

Why was I told that I have pulmonary hypertension if I have diastolic heart failure?

A critically important test to evaluate patients with shortness of breath is an echocardiogram (ultrasound of your heart). This test accurately measures the squeeze or systolic function of your heart. The relaxation phase is more difficult to accurately measure. As a result it is often not measured. The estimated pressure in the pulmonary arteries is also measured (though it is often inaccurate). When a cardiologist sees normal squeeze (systolic function) of the left side of your heart and an elevated estimated pulmonary artery pressure they often make the mistake of labeling this problem as pulmonary arterial hypertension. Patients are then told that their heart is normal. When a pulmonary hypertension expert reviews the information, we look for other attributes of the echocardiogram to help uncover the real problem (diastolic heart failure).

Findings on your echocardiogram that suggest diastolic heart failure are listed below. There is no one finding – but rather a collection of findings in combination with your other attributes.

- Left ventricular hypertrophy (abnormal thickness of the left ventricle)

- Delayed relaxation phase of the left ventricle (if it was measured)

- Increased size of the left atrium (top chamber on the left side of the heart)

- Normal size and function of the right ventricle (heart chamber that pumps blood through the pulmonary arteries)

- Estimated pressure in the pulmonary arteries that are less than 50

For example, if I am seeing a patient who is a 65 year-old woman who weighs 205 pounds and has hypertension, diabetes, and sleep apnea the odds strongly favor diastolic heart failure over pulmonary arterial hypertension. If the echocardiogram shows normal size and function of the right ventricle and only mildly elevated estimated pulmonary artery pressures then the correct diagnosis is even more likely to be diastolic heart failure and not pulmonary arterial hypertension.

Who needs a right heart catheterization?

When the data are not clear then I rely on right heart catheterization to help me determine the correct diagnosis. There are patients that clearly have diastolic heart failure and not pulmonary arterial hypertension who do not need a right heart catheterization. If I am not sure then I often repeat an echocardiogram with special attention to certain measurements. If it remains unclear then I usually proceed to right heart catheterization.

Can you have both pulmonary arterial hypertension and diastolic heart failure?

Yes. In fact, we often see these two problems co-exist. However, after careful testing it is usually clear which is the bigger problem. Click here to read more about the combination of diastolic heart failure and PAH.

What are the treatments for diastolic heart failure?

I start with addressing all of the risk factors for diastolic heart failure. Eating a healthy diet and losing weight are a top priority. If you have diabetes then we focus on good control of your blood sugar. Sleep apnea is treated if present. Blood pressure is controlled. Many patients with diastolic heart failure eat foods that are high in salt and consume too much fluid. Goals are less than 64 ounces of fluid (less than 2 liters per day) and less than 2,000 milligrams of salt (sodium chloride). Next we focus on diuretics. The majority of patients with diastolic heart failure retain salt and water. We help solve this problem by starting or adjusting diuretics (medications that cause you to urinate—pee out all the salt and fluid you are retaining). Exercise is also important. We encourage our patients to begin an aerobic exercise program such as walking daily.